Country Music’s Outlaw Legacy, Behind Glass

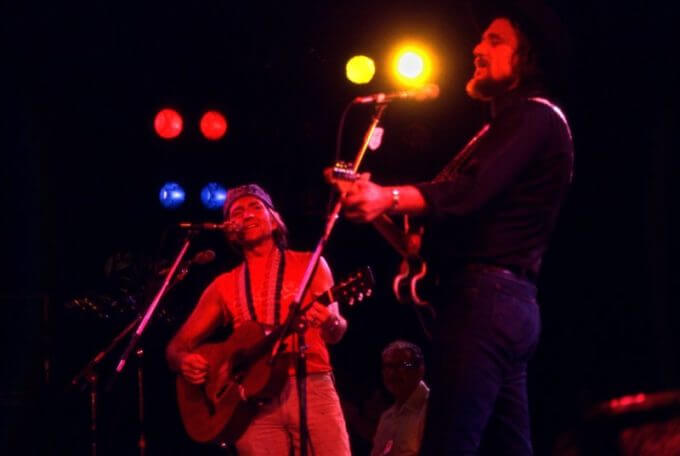

Leonard Kamsler/Courtesy of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

By Jewly Hight, NPR Music

Few periods of country music history have received more popular attention (or rock press) than the outlaw movement. Decades later, its towering personas — Willie and Waylon chief among them — remain a subject of fascination, immortalized as leathery, long-haired stoners and speed freaks who operated entirely outside the law of the country music establishment. By the time the movement had run its course, it had become a marketing tool for the industry. These days, the “outlaw” label gets applied to all sorts of artists who are viewed, or want to be viewed, as rejecting commercialism, slickness or docility, and serves as branding for everything from a satellite radio station to a cruise and entire categories of online merch.

There’s undeniable appeal to heroic tales of musical rebellion, but the way that idiosyncratic music-makers and conservative executives interacted during that era was actually far more complicated. Tyler Mahan Coe, creator of the podcast Cocaine & Rhinestones, has made it his mission to sort reality from mythology through deep, irreverent dives into pivotal figures, sounds, songs and scandals from country music history.

Fittingly, Coe’s got his own peculiar, evolving relationship with the notion of the Nashville establishment. Following a visit to the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, he says he’s not yet used to receiving a warm welcome. “I’m surprised they let me in that building every time I go down there,” he smirks.

He’s joking about his ignominious pedigree; he carries the family name of one of country music’s more notorious provocateurs, his dad, David Allan Coe, with whom he once toured as guitarist. But that didn’t deter museum staffers from reaching out to the younger Coe, offering access to research materials, once they heard his podcast.

The first episode went live last October. During it and every episode after, Coe beseeched his listeners to geek out about the week’s topic with a friend. Midway through the season, he lamented the podcast’s lack of mainstream media coverage. Within months, he was reeling a bit from the intensity of the buzz it was generating.

People were responding not only to the fact that he’d filled a previously vacant niche in the podcasting landscape, but that he’d found a compelling tone and approach. On one hand, he treated his subject matter with a serious-minded thoroughness that we’re more prone to expect from an experienced journalist or academic than a self-educated upstart. On the other, he had the bristly enthusiasm and brashness of someone who staked his authority on firsthand knowledge and personal investment, who relished collecting and correcting country lore. When he feels like someone’s spreading inaccuracies, he says, “I can’t let it go.”

Coe was anxious to see what the museum’s brain trust would do with an exhibit titled “Outlaws & Armadillos: Country’s Roaring ’70s,” how it would tackle prevailing notions of country outlaws and the cultural rivalry between Nashville and Austin. So he joined me for a tour guided by Peter Cooper and Michael Gray, two of the curators responsible for the ambitious project.

Coe is well aware that the role he plays in contextualizing history is far different, and more that of an outsider, than the role of the museum’s historians and curators, who shoulder responsibility for judiciously shaping, reshaping and institutionalizing the country music narrative. Its exhibits explain the folk roots of what’s become a massive commercial industry and lay out a lineage that links together stars of far-flung eras.

We convened a week and a half ahead of the grand opening. Heavy black sheets separated the area from a nearby corridor filled with browsing tourists. Here and there, post-it notes affixed to the glossy signage specified final fixes to be made to the text.

Right away Coe spotted the rusty, cylindrical shape of a moonshine still and strode toward it, asking, “What is that?”

Bob Delevante/Courtesy of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

Cooper informed him that it was the property of the singer-songwriter Tom T. Hall and the Rev. Will D Campbell, then directed our attention to other artifacts sharing the display case, including battered six-strings belonging to Shel Silverstein, who wrote country songs when he wasn’t authoring children’s books and Playboy columns, and Jack Clement, the impish producer of a staggering array of acts, that were passed around at guitar pulls and saw plenty of communal use.

Elsewhere were such rarified items as Kris Kristofferson’s military jacket, coveralls that Lubbock-bred progressive country figurehead Joe Ely wore when working for the circus, a wooden case of harmonicas belonging to longtime Willie Nelson band member Mickey Raphael, the door of the Luckenbach dancehall depicted on the cover of the Jerry Jeff Walker album Viva Terlingua and a taxidermied armadillo from the Austin nightclub Armadillo World Headquarters.

Coe has made it known in the “liner notes” to his podcast—the segments appended to each episode in which he credits his sources and explains decisions on which he expects to be challenged—that he’s wary of interviewing the musicians and business types he discusses, or people who knew them, lest he be diverted from the truth by his interviewees’ charisma, axe-grinding or desire to cast themselves or loved ones in a positive light. But assembling an exhibit of this magnitude required no small amount of outreach and diplomacy on the parts of Gray, Cooper and their colleagues.

“A lot of our job was building trust with folks in Austin,” Gray told us. “We didn’t know a lot of those folks, so we spent a couple of years just with stewardship and building those relationships, building that trust that we would tell their story correctly and [they could] trust us with their precious artifacts. Most people were eager to loan us things.”

They faced the challenge of capturing a dynamic, amorphous moment in a tangible, accessible way.

Standing in the gallery, surrounded on all sides by video footage of musical performances, Cooper and Coe were in agreement that no one sound or style defined the outlaw movement.

“You ask some people, and they’re gonna say a phaser pedal,” Coe mused, “but that’s just because they’re thinking of Waylon Jennings.”

“The whole point was to not have a sound,” Cooper concurred. “The point was to go in and get your own sound.”

A 36-track compilation album accompanying the exhibit underscores the point, placing iconic, raggedly rendered story-songs alongside eccentric string band grooves, roadhouse romps, raucous country-rockers and plaintive balladry.

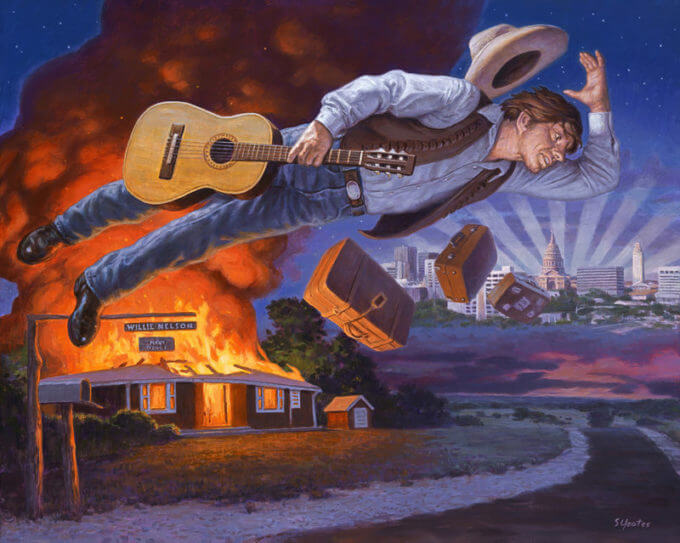

Courtesy of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum

The exhibit leans on the trajectory of a portion of Nelson’s career for a loose sense of chronology, beginning with a clip of him singing in his clean-cut Nashville days, passing by a fanciful painting of him flying away to Texas the night his Tennessee hog farm burned down and bits and pieces of his thoroughly casual ’70s stage attire and arriving at the jazz and pop standards he decided to record after nearly a decade’s worth of folk-country-sounding concept albums.

“You could talk about Willie growing out his hair and wearing tennis shoes and a bandana and all that in the ’70s,” Gray noted, “but showing what he looked like in the ’60s, in his suit and his [neatly combed] hair, kind of shows the transition.”

More than anything, the exhibit seeks to capture a sense of momentum and exchange, of the scene-building done at guitar pulls, parties, recording sessions, shows and festivals. Some of the music-makers depicted in it made decisive migrations, Nelson back to Texas and Mickey Newbury, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt and Rodney Crowell from the Lone Star State to Nashville. But many didn’t necessarily feel the need to camp out in one territory or the other. Austin, and its surrounding area, had a robust live scene encompassing hippie kids and rednecks, while Nashville had the studio facilities, industry infrastructure and pro songwriters.

Coe had caught glimpses of several mentions of his own father by the time we were finished perusing for the day, but he had other reasons to be satisfied with what he’d seen and heard. He and I sat down together in a tiny, glassed-walled conference room of a building housing shared work space after perusing the “Outlaws & Armadillos” exhibit. Grazing on grocery counter sushi, he declared, I feel like the approach taken there is the approach that I would take to doing something like this. Which is, ‘I’m gonna have to say some things that some people think are the opposite of the truth.’ But it’s more important to history that the real story gets told than it is that someone’s feelings don’t get hurt because they’ve had it wrong in their own way of thinking about it.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

What popular narratives about outlaw country were you mindful of going into the exhibit?

I see a lot of people who have this idea of, “It was all guns and drugs and people getting shot and all this craziness.” OK yeah, but not any more so than the entire history of country music. This has always been that culture. It’s just there was a little window of time there where the image sort of embraced that aspect of these outsider personalities, and even inflated it.

You’ve pointed out in the podcast that the lasting significance of particular moments, movements and artists emerges over time. And so does mythology.

The scope of my interest in the podcast ends at the year 2000, and it’s because we don’t have any idea what’s going on now until it’s all over. You’ve got a bunch of people running their mouths right now, acting like they know what they’re talking about. And then in 15 years, and in 50 years, we’re gonna find out how much they don’t know what they’re talking about.

I think one of the biggest misconceptions people have is that there was some great animosity between everyone working in Nashville and everyone working in Texas — or just outside of Nashville. And that’s not really the case, because for one thing, the Nashville industry was built by people, many of whom were worshipped by the artists working in the outlaw movement. Bobby Bare was as establishment as it gets. Willie Nelson himself was as establishment as it gets.

You don’t get much more establishment than [Nelson and Waylon Jennings’ manager] Neil Reshen coming to Nashville to lay down the law for his artists. That’s the establishment fighting the establishment on behalf of the artists. Anyone who’s seen behind the curtain of the music business knows that’s what happens every single day is the establishment fighting the establishment on behalf of their vested interest. That’s something I think is there for everyone who would like to read in the exhibit, at least in a subtle way.

Since there really isn’t a uniform stylistic stamp on the music, I looked for the connecting threads and timeline as I walked through.

I was really happy that they used [the album] Wanted: The Outlaws as sort of like, “OK, this is about over by the time it gets to this point.” The common perception is probably that that album began the outlaw movement. That has been my experience in speaking with country music fans for my entire life. They wear that t-shirt of that album cover and talk about how great the outlaw country movement was. I’m certainly not disparaging this in any way. I’m not trying to, like, myth-bust this. It was great music that they were making, but the reason why the exhibit sort of tapers off there is ’cause the artists wanted to taper it off there. They were like, “This is getting out of hand.”

You can’t spell it out more directly than Waylon’s song.

It shouldn’t be read as criticizing it, or somehow saying that it was fake, therefore not good. The artists saw it had run its course.

What forces do you see converging in the outlaw moment? How much did it matter that some country artists were developing high-concept visions for their albums or placing more value on the work of narrative-driven singer-songwriters? Or cultivating rougher stage looks?

I think there really are a lot of factors. The conversation that I was most excited to be having, even though it didn’t really get to a solid answer, was when we were talking to [curator] Michael [Gray] about [record man] Shelby Singleton’s role in sort of anticipating this whole vibe, the zeitgeist of this. I don’t see how you could argue that [Singleton] didn’t see this coming when he signs David Allan Coe and puts out an album called Penitentiary Blues in 1970. But there was something that let people know that this was about to be the thing that happened. There was something in Nashville that people could see gathering. And it really is ephemeral. It’s sort of like an attitude, like a feeling in the air or something.

When you get Willie going down to Texas, he’s not really involved in the album-making machine, and he’s making something happen in places like the Armadillo World Headquarters. He’s got this thing happening and people are responding to that. They’re not showing up because they heard this on an album and they want to see if he can play it live. They’re just showing up to see what’s happening in the room right now.

So then it flips and it becomes a question of, “How do I get what’s happening in this room onto an album so everyone who wasn’t in this room can experience it?” And that’s when you run into a problem coming back to Nashville, trying to explain to a guy wearing a suit behind a desk, who’s never been to the Armadillo World Headquarters, “No, dude, if we make it sound like this, people will buy it.” That’s the real shift that happened, was paying attention to what was happening everywhere else. That’s the problem that comes with being Nashville, Music City: “We know how this is done. We know everything there is to know about this.” And I think that’s really what we’re looking at here, is this sort of [acknowledgement]: “Maybe we don’t know everything. Maybe we should let these people play around a little.”

It wasn’t a complete withdrawal from the music-making system so much as a reckoning within it.

It really did happen from within the system. And the system was smart enough to play the role of the bad guy, if needed. The president of a record label doesn’t care if Waylon Jennings’ fans think he’s a cool guy or not: “Waylon, if you’re gonna sell albums, we’re good.” It’s more of a collaborative effort than I think people realize.

I appreciate the fact that you regularly place artists in conversation with the cultural landscape, market factors and industry realities in the podcast. It’s simpler to avoid all of that context and spin narratives of artistic heroism.

I think it’s an extremely naïve perspective to take on it, to assume that an artist doesn’t care if they’re moving units or not. Of course they care, because if they don’t move units, they don’t get to do this anymore. If you just want to play guitar on your front porch, no one’s stopping you from doing that. As soon as you come and get into this game, it’s art and commerce.

Some of the other exhibits that have been staged in that space featured the perspectives of industry execs and producers a little more prominently. Those aren’t the voices narrating this story.

I don’t know if you noticed, but right when you came out of the exhibit they made a big deal about the photo of Waylon being right there. Right behind it was the Billy Sherrill [section of a separate exhibit].

Billy Sherrill is someone I love talking about in relationship to the outlaw era, because he’s generally seen as the anti-outlaw. He’s generally painted as one of the bad guys in the story of how [Nelson’s album] Red Headed Stranger came to be released. He’s supposed to be one of the guys who hated it and said that it sounded like a demo. I don’t doubt at all that he said that, because if you go back and listen to that album with the ears of a producer of that time in Nashville in country music, that s*** sounds like a demo. It sounded that way on purpose. It wasn’t like Willie doesn’t know how to make an album. Willie made the album he wanted to make, and history proved him correct.

John Shearer/Getty Images for Country Music Hall Of Fame & Museum

But also Billy Sherrill produced Johnny Paycheck. You can’t say that that didn’t happen. So Billy Sherrill is as much a part of the outlaw movement as Jack Clement. [Note: Like Sherrill, Clement bridged several different eras and styles of production in Nashville. In the mid-’70s, he produced Dreaming My Dreams for Waylon Jennings.] If you want to say that Jack Clement was a part of the outlaw movement, you have to say that Billy Sherrill was too. Also all the David Allen Coe albums that everyone loves holding up as a picture of such a crazy traditionalist move, [much of that] was produced by Billy Sherrill.

Did you expect to see more on your dad in the exhibit? Didn’t they say that they tried to get one if his rhinestone suits?

They tried. It’s difficult. My father has filed bankruptcy, so you lose a lot of stuff. He has defaulted on payments for storage units and lost who knows what. Money has been a problem for him. He’s not a very responsible person, you know?

I felt like there was an appropriate amount of David Allan Coe in the exhibit if your gauge of it is fame. He’s certainly not as famous as Waylon or Willie. He’s probably approximate to Guy Clark or Jerry Jeff Walker. It’s hard to talk about fame quotients. I don’t really know if I’m right about that or not.

They have the promo footage of “Penitentiary Blues,” which I think is indicative of their awareness. That’s not a country album. It’s electric blues. It was released on an R&B label, not on a country label, and it wasn’t trying to be country. It was made in Nashville and the whole story was, “Here’s a new white blues singer who has been in and out of prisons his entire life.” There’s no way that doesn’t go into the ingredient list for outlaw country. That’s in the exhibit, and I think it should be.

A lot of the artifacts underscored how this wild-eyed, freewheeling socializing and music-making music coexisted.

What’s funny is what you just described is very much my perception of country music in Nashville from the beginning. If you read about Tree Publishing, particularly the time when Don Gant was in there taking care of business, doing very well at his job in a commercial sense, you go in there after hours and he’s gonna have 25 people in his office. They’re going to be smoking pot and they’re going to be listening to the initial pressing of an album that somebody’s been working with or they’re going to be passing a guitar around and just hanging out. It’s a party, but out of that party comes hit records. That’s really always been my understanding of how at least the songwriter and publishing world in Nashville [worked].

Was there anything that struck you as being especially new about the museum’s take on this era?

Honestly, the entire exhibit itself you could think of as new, in that it is what we think of as the country music establishment recognizing what we think of as the country music anti-establishment. I am not aware of the museum really featuring outlaw country to this extent before. I’ve only been back in Nashville for five years, so I’m not super aware of what they’ve been doing [before that].

And placing ’70s Nashville and Austin side by side, that’s new.

If a picture [in the exhibit] was taken in Nashville, it was someone from Texas, or if it was taken in Texas, there was someone from Nashville in the picture, so the lines really are blurry.

There’s that entire panel of artifacts from Texas figures like Doug Sahm, Jerry Jeff Walker and Joe Ely.

Doug Sahm is also someone that I don’t think a lot of people — not necessarily country music nerds, but music nerds who picture him with Sir Douglas Quintet, I think his inclusion might come as a surprise to people. But that’s also kind of funny because they have the [western stage] suit that he wore as a little kid. I mean, no one could have predicted the outlaw country movement when he was getting started. [Note: Sahm was a pedal steel prodigy and performed alongside Hank Williams. Sr.]

Right next to his stuff was a small Freda and the Firedogs display. I think it’s significant that a band that released zero recordings but impacted Austin’s live scene is included.

This is something that I think can get lost in a lot of conversations like this. We have a general tendency to talk about albums as if they are the only thing that matters. And all that an album is is just a fraction of what was going on at the time.

But this exhibit is focused very little on the actual music. It’s so much more about the culture that was happening around it.

The scene.

Willie Nelson’s picnic and the fact that it was country music that they were putting in the center of this conversation, and it’s drawing all these other types of people. To me, that is the outlaw country era really more than the albums. It’s the culture shift around it.

The Fourth of July picnic is a lasting institution. It’s still happening every year and still seems to represent more or less the same cultural mash-up. That’s the one place where the exhibit nods to an ongoing lineage, mentioning artists like Jason Isbell and Eric Church playing it in recent years.

There’s a great story [that I’ve heard] about George Jones playing one of the early picnics. George was just sweating bullets the whole day because he’s looking at all these people walking around with their shirts off, long beards, long hair, topless women, people smoking pot openly. He’s in a rhinestone suit and his band is in matching rhinestone suits, and he’s like, “These people are gonna tear me apart. I’m gonna get up there and people are gonna think I’m a dork.” And he gets on stage and pretty much everyone agrees that he was the hit of the whole day, that he was everyone’s favorite act.

It’s remarkable that rednecks and hippies were inhabiting the same live music spaces, the same scenes. Willie Nelson succeeded in making himself all things to all people, and that’s still the way he’s written and talked about.

Willie Nelson was the main focal point of the outlaw movement, and the outlaw movement reached out its hands to every other music community and said, “You can come hang out here.” That’s how you end up with Willie Nelson as one of the most recognizable figures in country music history. It’s because of the vibe of freedom, that these are people who are doing it their own way.